Mary Cassatt: painting the modern woman

Born to a wealthy family in Pittsburgh, Philadelphia in 1844, Mary Cassatt began her training at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1860, when she was 16, one of the few institutions where women were allowed to study. She moved to Paris in 1865, with her indomitable mother Katherine Kelso Johnston acting as a chaperone. Here, Mary set about studying L'art pompier - academic and historical paintings. After a return to America to avoid the Franco-Prussian war, she returned to Europe to spend time studying the great masters in Italy and Spain, a period in which she was still under the spell of realism, the gritty style pioneered by Gustave Courbet.

‘Woman in a Riding Habit (L'Amazone).’ (1885/9) by Gustave Courbet.

Mary Cassatt said this work was ‘the finest woman’s portrait Courbet ever did.’

After her return to Paris, in 1872 Mary had ‘Two Women Throwing Flowers During Carnival,’ accepted by the Salon - an achievement almost unheard-of for a young American of either sex. Two years later Edgar Degas was taken to see Cassatt’s ‘Ida,’ at the Salon by the engraver Joseph-Gabriel Tourny. Degas commented: ‘C'est vrai. Voilà quelqu'un qui sent comme moi.’ (‘It's true. Here is someone who feels as I do.’)

‘Two Women Throwing Flowers at the Carnival.’ (1872)

By 1877 Cassatt's work had become more and more Impressionist and had been twice rejected by the Salon. It was, Degas thought, time to call. In her studio at the edge of Montmartre, he found himself treading on Turkish carpets, peering at beautifully framed paintings hung against tapestried walls and lit by a great hanging lamp. It was his preferred ambience. Before he left, he invited her to exhibit with the Independents. ‘Most women paint as though they are trimming hats,’ Degas said. ‘Not you.’

Reminiscing later in life, Cassatt still had strong feelings about the decision; in 1912 she told her biographer, Achille Segard, 'I accepted with joy. I hated conventional art. I began to live. How well I remember seeing for the first time Degas’s pastels in the window of a picture dealer in the Boulevard Haussman. I would go and flatten my nose against that window and absorb all I could of his art. It changed my life. I saw art then as I wanted to see it.’

‘Before the Mirror.’ (c1889) coloured pastel by Edgar Degas

While the impressionists were not widely known for their commitment to the advancement of women (Renoir asserted that he considered ‘women writers, lawyers and politicians ... as monsters and nothing but five-legged calves. The woman artist is merely ridiculous’) Paris was, at that time, a vibrant and lively scene for women painters as well as for men.

As a woman caught up in this period, Cassatt was by no means alone. There is an overlap between her, Berthe Morisot, Marie Bracquemond, Eva Gonzalès and even Suzanne Valadon – all painted women freed of the male gaze with paintings that illuminate the internal lives, relationships and realities and outside of their artistic practices, they actively advocated for women’s suffrage and girls’ education.

In Cassatt’s 1878 painting ‘In the Loge,’ she captures the spectacle of looking in late 19th-century Paris through a complex web of gazes. As the viewer, we take in the side profile of a woman at the opera who peers through her opera glasses at an unseen audience member across from her.

‘In the Loge.’ (1872)

In the background, a man leans from his box in an effort to spy on the woman through his own glasses. The image is a scene of modern life, a portrait that captures the self-assuredness of the female spectator. Cassatt painted balcony scenes over and over again, it conveniently combined aspects of spectacle and voyeurism.

That same year she collaborated with Degas on probably the most important picture of her career. ‘Little Girl in a Blue Armchair.’ Degas’ influence is evident in the asymmetrical composition, casual treatment of the sitter, and the cropping of the image, a hallmark of the Japanese prints which were then flooding Paris.

It was the type of work that spurred critics to take notice of Cassatt. When it was entered along with eleven of her other paintings into the Fourth Impressionist Exhibition in 1879, her debut impressionist show, a critic wrote : ‘It is equally impossible to visit the exhibition without finding most interesting Mlle. Cassatt's portraits. An utterly remarkable... sense of elegance and distinction marks these portraits. Mlle. Cassatt deserves very special attention..’

‘Little Girl in a Blue Armchair.’ (1872)

So began a 40-year relationship. At first Degas and Cassatt were seen everywhere together. Degas produced a series of pastels, drawings and etchings of Cassatt at the Louvre; viewed usually from behind, slim and elegant, she is absorbed in the art before her.

Like every artist, Cassatt’s paintings can be uneven, her work occasionally succumbs to kitsch but in her best work, which seems genuinely radical even today, we are aware of tension, described by one male writer as a ‘flutter of nerves,’ as she depicted the excitement of women on the verge of the 20th century, the moment before the bonnet and the stays were finally torn off and thrown away for ever.

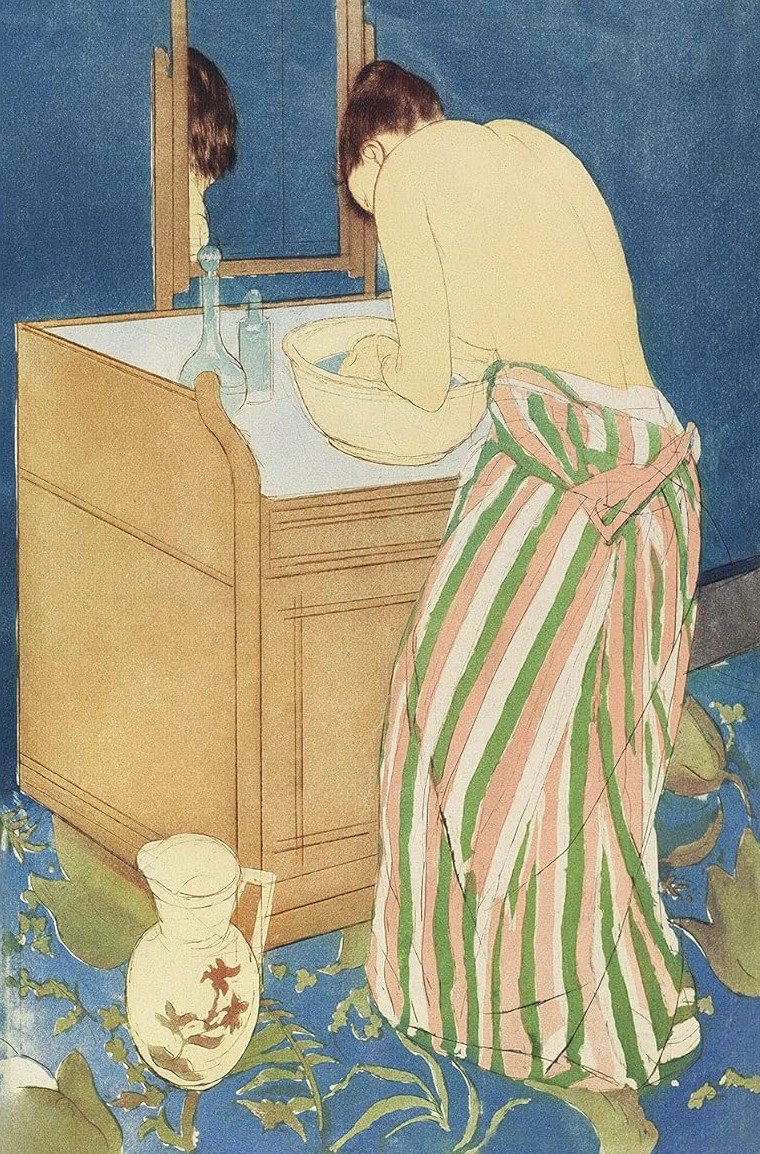

‘Woman Bathing.’ (1891) coloured print

It was the 1889 exhibition of work by the Société de Peintres-Graveurs at Durand-Ruel gallery which saw Cassatt pivot away from painting. The show sparked a renewed interest among French artists in printmaking. Cassatt’s dry-point etching technique - a method that gave her work an immediacy that Charles Baudelaire would have applauded and which the influential critic Félix Fénéon is said to have exclaimed: ‘we have perfection.’

As one of Cassatt's early experiments with printing in colours, she chose the 'à la poupée' method in which ink is applied locally to areas of the plate before printing – this helped to treat her prints as unique works of art as each one was different, it also aided the popularity of Mary’s work - it was an ideal medium for capturing intimate, domestic moments at which she excelled.

‘Young Woman in a Black and Green Bonnet, Looking Down.’ (c1890) coloured pastel by Mary Cassatt

She was also becoming increasingly preoccupied with pastels and by the 1890s it had become her primary means of expression - it allowed her to get closer to depicting women and children with a tenderness and poignancy.

Her final large-scale painting was a vast mural for the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. Once installed, it astonished viewers with its allegorical depiction of larger-than-life girls and women jointly pursuing scientific, artistic, and cultural achievements. When asked why she had excluded male figures from her vision of contemporary womanhood, Cassatt replied, ‘Men, I have no doubt, are painted in all their vigour on the walls of the other buildings.’

As well as her commercial and critical success as a painter and printmaker, Mary Cassatt helped form contemporary taste. It was under her tuition that the Havemeyers, the American collectors, acquired the great El Grecos and Goyas that can now be seen in the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

Failing eyesight severely curtailed Cassatt’s work after 1900. She gave up printmaking in 1901, and in 1904 stopped painting commercially. She spent most of the First World War in Grasse and died in 1926 at her country home, Château de Beaufresne, at Le Mesnil-Théribus, Oise.

My thanks to Tobin Auber for proof-reading this essay

* If you can afford to and if you think my essays are valuable and would like to support the writing of more, please consider buying me the equivalent of a cup of coffee by clicking this link https://buymeacoffee.com/richardmorris